When the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA) launched 15 years ago, it was extremely hard to find substantial narrative evidence of the lives and voices of South Asian Americans. In general, you’d be hard pressed to find much evidence of South Asians in any US history textbook. Throughout it’s existence, SAADA’s goal is make sure these voices are not only heard but given historical context and archived for future generations. As part of the 100th anniversary of a Supreme Court ruling that once banned South Asians from being US citizens, we wanted to share a story from our LPC collaborator SAADA’s archives that deserves to be absorbed by all Americans.

United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind

by Emmett Haq, Education Outreach Coordinator, SAADA

Many Americans have no idea of the scope of our historic battles over immigration restrictions, nor of how disproportionately they have impacted communities of color. One hundred years ago this month, the U.S. Supreme Court barred all South Asians from becoming American citizens—and, taking things a step further, applied the decision retroactively, denaturalizing dozens of South Asians already living in the country as citizens and leaving many of them entirely stateless. The unanimous decision reached in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind on February 19, 1923—though it remains little-known among the general public—deserves a closer look in today’s context, as we prepare to mark its centennial anniversary.

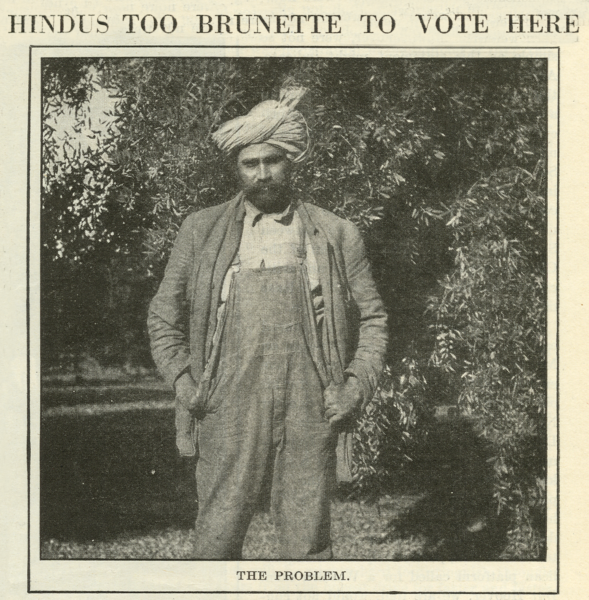

Photo is from Article written March 10, 1923 in issue of The Literary Digest

The man at the center of this case, Bhagat Singh Thind, was an immigrant from what was then called British India, who arrived in the US in 1913. He served as a sergeant in the US Army during World War I and after his subsequent honorable discharge, Thind was granted American citizenship in 1918. However, despite his service, his citizenship was subsequently revoked by the Bureau of Naturalization multiple times. He was first denied citizenship because he was not considered a white man by the government’s racial categorization system at the time, then for alleged membership in the Ghadar Party (a revolutionary organization dedicated to freeing India from British colonial rule). As the Bureau continued to appeal to higher and higher courts, the case eventually made its way to the Supreme Court, which deliberated on whether Thind could be considered legally white. In delivering the court’s opinion, Chief Justice George Sutherland wrote: “The children of European parentage quickly merge into the mass of our population … [but] the children born in this country of Hindu parents would retain indefinitely the clear evidence of their ancestry.” Newspapers of the era made declarations that “our Western seaboard […] we find has a Hindu problem just as much as a Japanese problem,” topped with sensational headlines like “Hindus Too Brunette to Vote Here.” This verdict was unique in American history: though denaturalization was often wielded as a weapon against individual political dissidents, the Thind case and the infamous Chinese Exclusion Act remain the only instances of mass denaturalization on the basis of race.

The impact this ruling had on the South Asian community in the United States—at the time and even now—is hard to overstate. The men who had lost their citizenship (and it was men, for almost all South Asian women had been restricted from entering the country by preexisting regulations) were left stranded in the United States, having renounced their British citizenship before becoming naturalized here. They retained none of the rights afforded by naturalization, had little in the form of a support network, and were discriminated against on both legal and interpersonal grounds. The situation was so dire that at least one man, Vaishno Das Bagai, committed suicide as a result, asking “Is life worth living in a gilded cage?” in the note he left behind. This status quo remained for decades, until the introduction of a quota system with the Luce-Celler Act in 1946 and finally the rollback of restrictions with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. Of course, such draconian restrictions for such a lengthy span of time profoundly affected the demographics and history of today’s South Asian American community.

Bhagat Singh Thind himself was a complex figure, neither defined by nor able to escape his role in this high-profile struggle. In the modern day, he is alternately valorized as a hero or viewed as an assimilationist (among the limited subset of Americans who know his story in the first place). Thind’s reliance on his “high caste status” and supposed “Caucasian” race, like the arguments of Takao Ozawa before him and John Mohammad Ali after, was an attempt to use the tools available to him at the time—which ultimately demonstrated the consistent fruitlessness of such an approach. Despite his ostensibly legalistic methods, Thind remained a lifelong associate of the revolutionary Ghadar movement and is often referenced in the correspondence of U.S.-based advocates for Indian independence. Nevertheless, after his brush with notoriety in 1923, Thind largely retreated into life as a spiritual leader, eventually earning nationwide renown as a religious teacher and “spiritual scientist” before finally obtaining lasting citizenship through a New York state law that made all veterans eligible for naturalization in 1935.

SAADA firmly believes that histories like these have a serious impact on our lives today, and that knowing the painful stories of our past can help safeguard us from seeing them repeated. We have the unique privilege of hosting many letters, photographs, and other artifacts dating back hundreds of years (including the collected materials associated with Bhagat Singh Thind, Vaishno Das Bagai, and their families), many of which might have been lost entirely if not preserved in SAADA’s archive. Their legacy is one we can ill afford to ignore.