A home in Buffalo under more than 4 feet of snow – credit: Myles Carter

It’s hard to digest media in the past month and not be transported to one climate related disaster or another. Atmospheric rivers in California, winter bomb cyclones in the Midwest, and right before Christmas, an epic blizzard in Western New York that resulted in more than 30 deaths in the Buffalo area.

Invariably lower-income folks, and immigrant, BIPOC and Latinx communities experience worse outcomes in these increasing common major weather events, in part because of a lack of basic resource allocation, and that includes information. One Buffalo community member told us about the information gaps that contributed to the high death toll during the blizzard. “Some were systemic, and some were happenstance,” he said. Everything from the city failing to communicate enough to the local newspaper leaving its paywall up during the storm. The person said the outcome was not surprising in, “one of the poorest and most segregated mid-size cities in the US,” which has recently seen net population growth for the first time in decades thanks to the substantial growth of its immigrant communities.

We decided to turn our Listening Post Collective mic over to Buffalo based community advocate Myles Carter to talk about what he saw and did during the blizzard, and how a lack of information access contributed to the humanitarian crisis.

Information Whiteout

by Myles Carter, community advocate, Buffalo, New York

On Thursday before the storm hit, it was roughly 40 degrees outside and torrential rains began around seven in the evening. The rain never subsided, and around eight the next morning it began to turn into snow, quickly forming slush in the streets everywhere. I don’t know when the winds started, but they didn’t subside until early Sunday morning. My home lost electricity Friday evening, around six p.m. The thermal temperature outside was at least 20 degrees below freezing, not calculating the wind chill that brought the temperatures down to around -30°. The only heat we had was provided by boiling pots of water on the gas stove, and we resorted to hanging as many blankets and sheets over the windows and doorways as we had. My five children, myself and my mom slept in the living room huddled up to keep warm. We had one flashlight and three half used candles on Friday, more than what most people had in their homes. By Friday evening the entire region was paralyzed. I had several feet of snow at my house, and we hadn’t been able to see any of the neighbor’s homes since that morning due to the white out conditions and snow drifts that stood as tall as 6 feet in some areas.

Many people were not prepared for the severity of the blizzard we were hit with. There was no weather advisory sent through the Wireless Emergency Alert System, like with other less severe storms, the driving ban went into effect roughly 40 minutes before the blizzard hit, and many were in transit to and from their jobs and wound up stuck en route.

The city of Buffalo was equipped with four warming shelters, two of which lost power with no back up generator, and the other two quickly filled to capacity as conditions worsened on day one. Emergency services were overloaded, ambulatory vehicles were stuck and abandoned all over the city, and for the first time in Buffalo history all 12 fire trucks were stuck in the snow and incapacitated, unable to respond to calls.

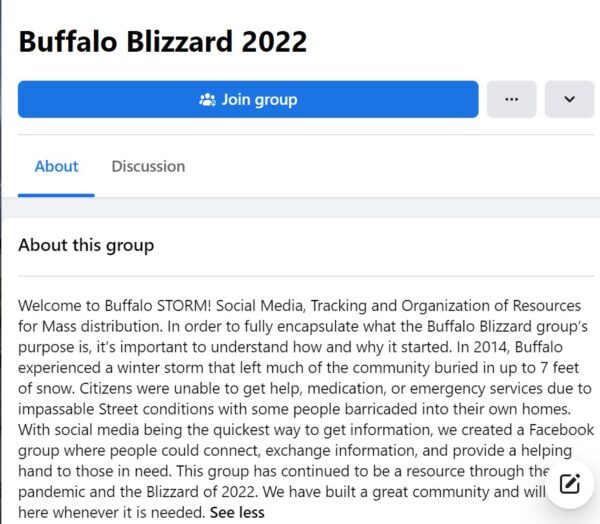

Through it all, there was a Facebook group put together called Buffalo Blizzard 2022 where people began sharing their stories, alerting of emergency situations and providing updates through the storm. Organically, neighbors were able to check on one another, provide shelter and necessities where emergency services were non-responsive.

Through it all, there was a Facebook group put together called Buffalo Blizzard 2022 where people began sharing their stories, alerting of emergency situations and providing updates through the storm. Organically, neighbors were able to check on one another, provide shelter and necessities where emergency services were non-responsive.

Much of the extent of damage and loss of life caused by the blizzard wasn’t known until after the storm subsided on Christmas day. There was no communication from emergency services or a broadcast system through government agencies, even today we don’t know all of the names of those who lost their lives.

Law enforcement and other government officials seemed more concerned with cracking down and prosecuting what they referred to as looting. While people were still in emergency situations, needing to be rescued and transported to the hospital, the police formed an anti-looting task force to enforce protections on property and resources that were desperately needed by the people.

Myles Carter helps a senior housing resident escape a building with no heat or electricity. photo credit: Madonna Wilburn

Meanwhile local residents, like Shakyra Aughtry, tried to respond to the human needs on the street. Aughtry heard the cries of an elderly disabled man outside her home on Saturday, stuck in the middle of the blizzard. Her partner had to drag the man’s half frozen body into their house in white conditions, and nurse him back to vitality. He suffered severe frost bite and was in a medical emergency. She pointed out that law enforcement was pursuing people suspected of looting down her very street, while she was unable to get emergency response for Joe, the man she and her partner rescued.

When the storm subsided, stores were closed, emergency services still non-responsive, and streets were paralyzed with snow several stores and building were broken into for shelter and necessities. Many of the hardest hit areas in Buffalo, one of the poorest and most segregated cities in the country, were predominantly Black and brown communities, where services were slow to be restored and roads last to be cleared.

Where formal resource and information networks failed the citizens of Buffalo, local individuals picked up the slack during the blizzard to help out their neighbors. Now we’re left thinking about how we can be better prepared in the future, from purchasing an extra canned good every time we go shopping to buying an extra candle every month. We also know there’s plenty of people who can’t afford to do that, and that even with proper warning, they won’t be able to stay prepared in the future. Minimally, we should expect to see notifications through the wireless emergency alert system sent out days before the storm, a driving ban should be in place hours before the storm, a plan should be in place for the seniors and most vulnerable and constant communication through the emergency broadcast system with updates on the storm and shelters.

Follow Myles Carter here